Is there a context beyond the act of compassion to view this radical shift in practice?

A quiet revolution is unfolding on the palates of the Bhutanese people. Beyond the mere act of compassion lies a complex tapestry of cultural, economic, and environmental considerations, weaving a narrative of transformation that resonates. There is a profound shift, a growing awareness of climate change.

In the tranquil village of Laptsakha, nestled in the Punakha valley, 45-year-old Sonam Choden’s journey reflects a burgeoning consciousness. A mere year ago, the notion of meat consumption was as distant to her as the peaks that kiss the sky. Yet, upon learning of the profound impact of meat on the climate, her culinary compass shifted. With a heart attuned to the rhythms of nature, she now treads lightly, reducing her meat intake in reverence for the earth. “We have to serve guests and have meat on special occasions, otherwise, there is no charm,” Sonam said.

Signaling not just sustenance but moments of celebration and communal bonding, Sonam Choden said, “a culinary ritual deeply ingrained in the fabric of Bhutanese society cannot be denied, especially on Losar and Tshechu.” Yet, for a greater concern, she shared, “If we are not able to stop completely, there is a need to reduce meat consumption to preserve our mother earth.”

Religious influence

Religion, too, paints strokes of influence on the canvas of Bhutanese cuisine. Beneath the eaves of Tharpaling Monastery, the voice of Khenpo Tshewang Sonam resonates with prophetic clarity. His sermons echo the consequences of consumption, stirring hearts to abandon the old ways in favor of a path illuminated by compassion and wisdom. Yet, amidst the sanctity of his teachings, Khenpo said, “The specter of temptation lurks, as the allure of indulgence threatens to eclipse the beacon of enlightenment.”

Beside Sonam Choden in Laptshakha, Pelden’s footsteps tread a path paved with tradition and reverence. For over a decade, 57-year-old Pelden has forsaken the consumption of meat, guided by the spiritual teachings that permeate the fabric of Bhutanese society.

In the village of Laya, once a bastion of yak slaughter, a newfound ethos of respect for life has taken root. As a custodian of livestock, in the village of Toka, Laya, Tshering grapples with how his livelihood is intertwined with the fate of meat sales. No longer do they harvest flesh through the blade’s edge; instead, they honor the sanctity of natural death, embracing a paradigm shift catalyzed by religious influence.

From the health point of view

Though Business Bhutan couldn’t contact any health experts, people are of the view that they should consume meat to maintain a healthy body. Especially, parents believe children should be fed meat at a growing stage.

In the realm of health, divergent voices echo in the minds of common people. While some extol the virtues of meat as a source of protein and vitality, others, like 79-year-old Dema of Shaba, Paro, find solace in plant-based alternatives. The debate rages on, a testament to the multifaceted nature of sustenance and well-being.

Once forsaken for more than a year, Sonam Choden had to consume meat after a doctor instructed her to follow a better diet. As a low blood pressure patient, she said, “Sometimes I feel weak” and resort to eating meat.

Meanwhile, Chimi Wangmo from Chungkha, Chukha, does not eat any meat, understanding it is sinful. Consuming meat doesn’t suit her body.

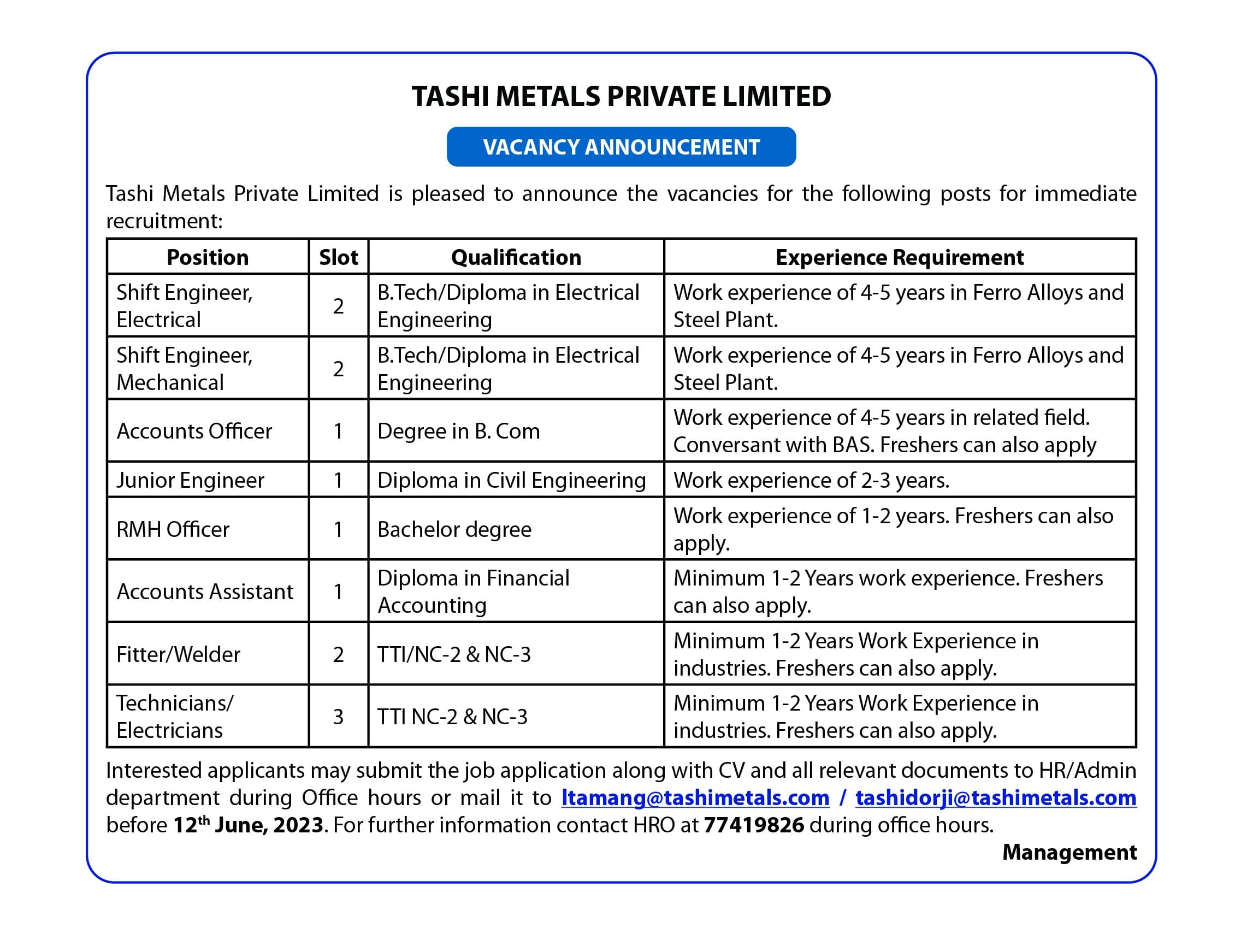

Statistics of meat imports and production

Meanwhile, as of 31 March, 2024, there are 425 meatshops in the country. Thimphu has the highest with 128 meat shops, followed by Phuentsholing with 51, while Gasa has the least with just one meat shop, according to the data from the Livestock Department.

699.84 metric tons (MT) of pork, 1,016.32 MT of beef, 161.32 MT of yak meat, 161.73 MT of chevon, 22.39 MT of mutton, 1,865.50 MT of chicken, and 192.97 MT of fish were produced according to the Livestock Census 2021, while 850.9 MT of pork, 696.8 MT of beef, and 107.2 MT of yak meat were produced in 2020. The import of bovine meat from India in 2023 has increased by 12,809 kilograms from 2022, as per the Bhutan Trade Statistics.

Meanwhile, the owner of Dagana Meat Shop in Bebena, Thimphu, Chandra Bdr Acharj, 41, observed that there is a decline in demand for meats. He imports meat from India. However, the demand for beef remains high.

Measures to reduce meat consumption

Amidst this kaleidoscope of perspectives, a call to action resounds. Atul K. Jain, a professor at the University of Illinois, Urbana-Champaign, heralds the transformative power of education.

So, the professor recommends educating people, particularly the younger generation, about the negative impacts of animal-based food. “Education can encourage the younger generation to change their attitude and behavior. It also helps them to make informed decisions,” the professor said.

Education empowers all people but especially motivates the young to take action. Through climate change education, people understand the impact of global warming today and increase “climate literacy” among young people.” I believe educational initiatives are central to making people sensitive to the current global epidemic. Termed ‘climate literacy’ helps foster an understanding of climate change and awareness of the current state of the world.

Therefore, developing climate mitigation strategies should follow a two-pronged strategy. First, calculate the complete GHG emissions from the production and consumption of total and individual plant- and animal-based foods, covering all food-related sub-sectors at local, country, regional, and global scales using a consistent framework. Such a complete estimate could help policymakers identify the significant contributing plant- and animal-based food commodities and the greatest emitting sub-sectors of individual food at different locations.

Second, policymakers should develop strategies to control GHG emissions from fossil fuel burning and other sources and from the production and consumption of total and individual plant- and animal-based foods, covering all food-related subsectors. However, this can only be accomplished based on spatially detailed results, which can help policymakers develop a strategy to reduce emissions from the top-emitting plant- and animal-based food commodities at different locations.

Yet, policy interventions must not falter in the face of complexity. Dr. Surendra Raj Joshi, the Senior Resilient Livelihoods Specialist for the International Centre for Integrated Mountain Development (ICIMOD), heralds the potential of Bhutan’s rich biodiversity as a beacon of hope in the quest for sustainable nourishment. With a harmonious blend of tradition and innovation, he envisions a landscape where nature’s bounty sustains both the body and the soul.

The Senior Resilient Livelihoods Specialist said that Bhutan has a rich agricultural biodiversity and natural products, which offer huge prospects for complete food (protein, carbohydrate, and other essential ingredients) as well as nutraceuticals.

“Bhutan may promote bioprospecting, which is a systematic and organized search for useful products derived particularly from plants, as a nature-based solution to balance cultural traditions with the importance of adopting environmentally friendly food choices. ICIMOD is interested in promoting this initiative together with national agencies in Bhutan,” Dr Surendra Raj Joshi said.

The Senior Resilient Livelihoods Specialist said that policy interventions are required to harness the potential of Bhutan’s rich biodiversity, creating an enabling environment for the collection, processing, and value addition of bio-resources, including wild edible fruits, vegetables, and medicinal plants.

Mountain communities are facing a myriad of challenges posed by climate change. The scientific assessment reveals that the cryosphere in the Hindu Kush Himalaya is warming two times faster than the rest of the world. There was a significant increase in glacier mass loss of around 65% in 2010 compared to the previous decade.

Meanwhile, a specialist from the Department of Livestock, Jigme Wangdi, said that the department is encouraging farmers to rear high yielding animals and practice balanced feeding to improve the digestibility of the animals. The department also resorts to renewable biogas.

The specialist said that though it wouldn’t be possible for Bhutan to grow lab and crop-based meat, Bhutan has National GHG Inventory, low emission strategies, and the Third National Communication to the UNFCCC.

As Bhutan charts a course towards sustainability, it is not merely a culinary evolution; it’s a testament to the resilience of the human spirit. The people continue to savor the flavors of compassion, tradition, and a future where sustenance sustains not just the body, but the very soul of the land they call home. Like Sonam Choden and Tshering, many are concerned about the impact of climate change and want to save their homeland for future generation maintaining the minimum global temperature.

However, meat consumption has been increasing around the globe despite the controversies surrounding its possible influence on health.

By Sangay Rabten, Punakha