Bhutan’s latest inflation data paints a picture of households under persistent, if moderate, pressure. According to a report released on January 30, 2026, the Consumer Price Index (CPI) shows that prices in December 2025 were 3.37% higher than a year earlier. While not alarming, the rise represents a meaningful shift in the cost of living — particularly because the largest increases occurred in essentials like food.

For the average consumer, a 3.37% rise is tangible. A basket of goods and services costing Nu 10,000 in December 2024 would cost about Nu 10,337 a year later. Across groceries, transport, clothing, and healthcare, such increases gradually tighten household budgets. December 2025 caps a year in which average inflation hovered around 3.5%, slightly higher than in 2024, reflecting a steady upward trend rather than a temporary spike.

A steady climb, not a shock

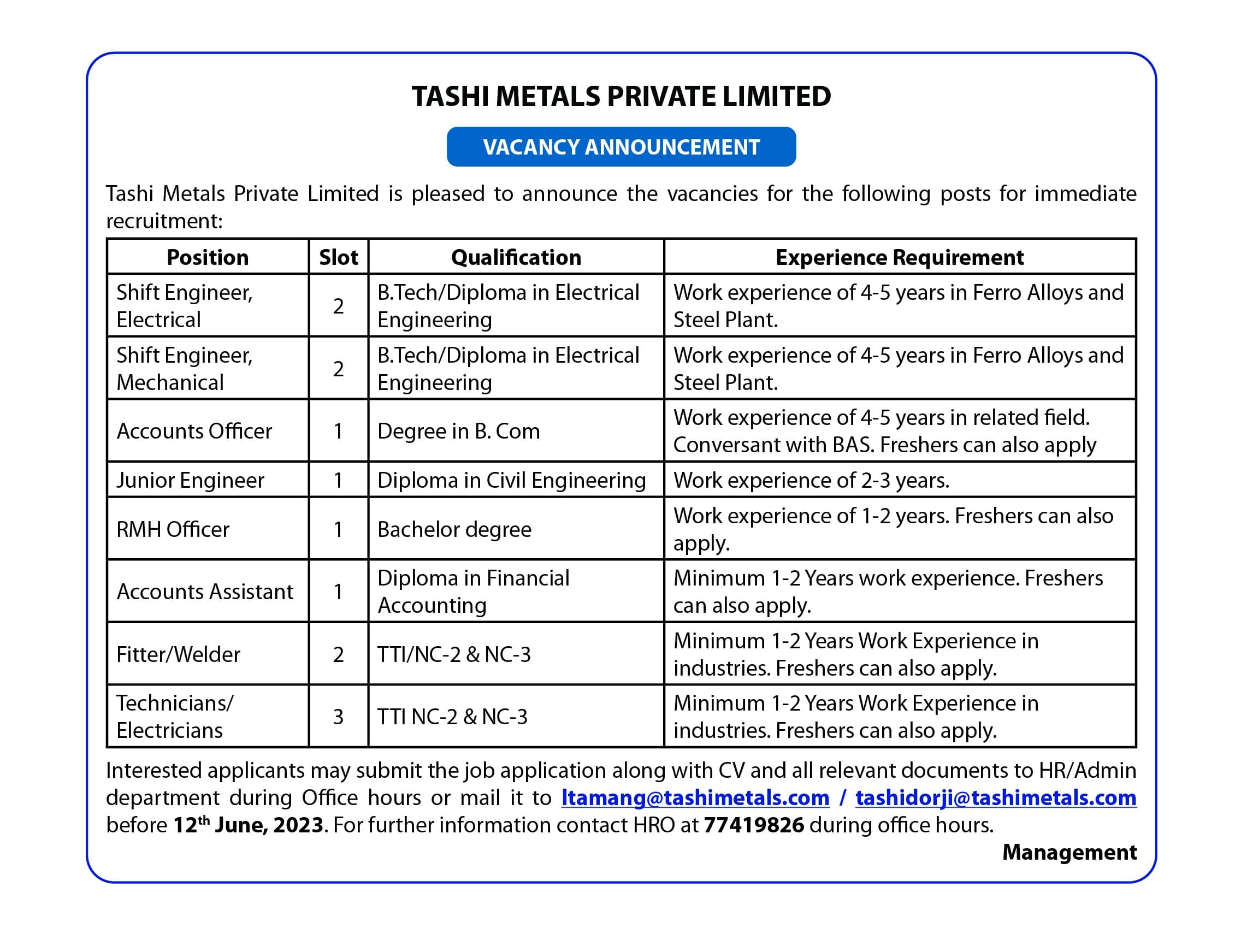

Bhutan’s national inflation rate climbed from 2.02% in December 2024 to 3.37% in December 2025. Economists would classify this as moderate — often associated with expanding demand and economic activity. Yet when price increases concentrate in necessities, households feel the strain more acutely. The CPI breakdown shows food and non-food categories moving unevenly. Food prices rose 4.36% year-on-year, outpacing the 2.7% increase in non-food items. Given that food accounts for roughly half of household spending, this imbalance magnifies inflation’s real-world impact. Families do not experience an abstract average — they feel it through the items they buy most often.

Food inflation hits hardest

The report highlights a 4.35% rise in food and non-alcoholic beverage prices, with staples such as rice, vegetables, and meat becoming noticeably more expensive. Alcoholic beverages and betel nuts rose 4.5%. Several forces drive this trend: higher transportation costs ripple through supply chains, seasonal bottlenecks restrict supply, and resilient consumer demand pushes retail prices upward. For middle- and lower-income households, food inflation is regressive. A large portion of income goes to groceries, so even modest increases require trade-offs, forcing families to cut discretionary spending, delay purchases, or dip into savings. For wage earners whose income lags price growth, real purchasing power shrinks.

Non-food prices: mixed pressures

Non-food inflation is milder but significant. Clothing and footwear rose 5.01%, while restaurant and hotel prices increased 3.81%, reflecting higher operational expenses passed on to consumers. Healthcare costs rose 3.95%, particularly sensitive because medical spending is often unavoidable. Transport prices increased 2.39%, driven by fuel and service costs, although some monthly relief occurred. Communication services remained stable, with a slight decline offsetting broader pressures. Combined, these figures indicate a consumer environment where essentials and semi-essentials are steadily becoming more expensive. Over time, these moderate increases accumulate, especially for households with fixed or slowly growing incomes.

Month-to-month and regional dynamics

December prices rose 0.38% compared to November. Food led with a 0.76% increase, while non-food prices edged down 0.05%, largely due to modest transportation relief. Month-to-month fluctuations may seem small but affect household budgeting, particularly during high-spending periods like holidays. Inflation varies regionally. The capital recorded 2.75% year-on-year inflation, with food up 3.7%, suggesting urban supply efficiency moderates price growth. The central region experienced the highest rate at 4.15%, driven by a 6.19% spike in food prices, putting households under greater pressure. The eastern region saw 3.12% inflation, while the western region registered 3.64%, both food-led. These disparities underscore that inflation is a lived, local experience influenced by transportation, market access, and supply dynamics.

Erosion of purchasing power

The Ngultrum’s purchasing power has fallen to Nu 53.5 relative to December 2012, meaning Nu 100 today buys just over half of what it did 13 years ago. Over the past year alone, purchasing power declined by about 3.26%. Even when wages rise nominally, real terms matter: if income growth lags price growth, living standards stagnate or decline.

What it means for households

For the typical Bhutanese family, December inflation translates into tangible pressures. Essentials are rising faster than non-essentials, forcing grocery budget adjustments or substitution strategies. Discretionary spending is increasingly compressed, affecting dining, travel, and apparel purchases. Budgeting discipline becomes critical, as households that track spending, compare prices, and plan purchases are better positioned to navigate rising costs.

A manageable but watchful outlook

At 3.37%, inflation remains manageable and does not signal an overheating economy. Yet the concentration of price rises in food — the most essential category — warrants attention. Persistent food inflation could further pressure household finances and widen inequality. Policymakers may need to consider supply chain improvements, targeted subsidies, or market interventions to stabilize essential goods. For consumers, the message is not alarm but awareness. Inflation steadily reshapes purchasing power and spending priorities. December’s data confirms that while price growth is moderate, its persistence is what matters most to everyday households.

Sherab Dorji

From Thimphu