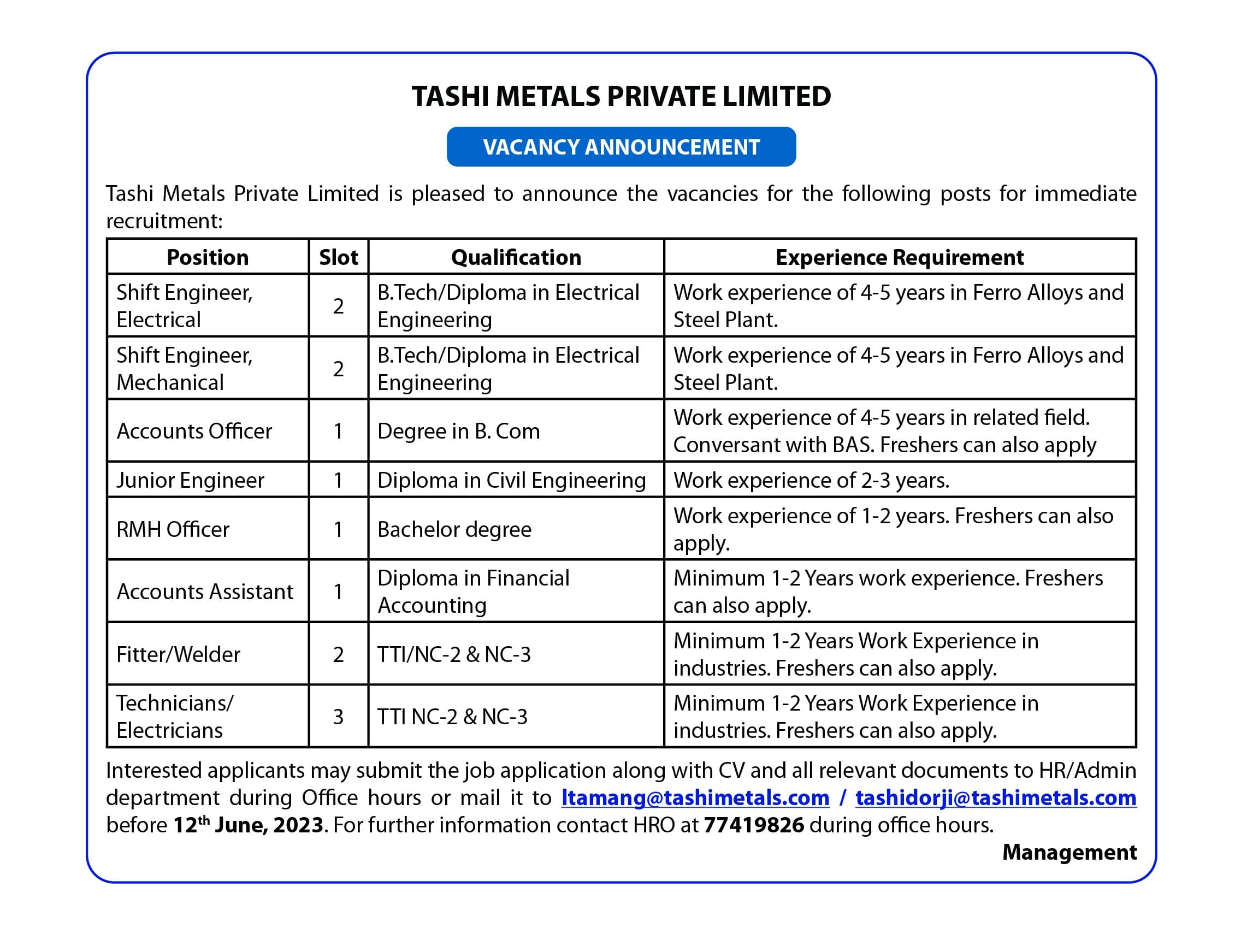

Much needs to be done on the economic front. This is especially after going by the

status of the country’s trade deficit as of mid-2022. When the country has been striving

hard to achieve food sufficiency, trade statistics show how seriously our imports have

been increasing against exports.

Bhutan’s quarterly trade deficit hit a fresh record of Nu 27.2bn in April-June as per

provisional trade statistics. This is the first occasion in six months this year that the

trade deficit has widened to an all-time high.

In June, including trade in electricity, the trade deficit is estimated at around Nu 21.2bn,

of which the balance of trade with India alone accounts for more than Nu 12bn in the

red.

A country experiences a trade deficit or negative trade balance because the import bill

is more than what it earns through exports.

Imports, however, hovered around more than Nu 13.2bn in both quarters, meaning that

the country imported goods worth more than Nu 35.8bn until June this year.

The tangible slowdown in exports, due to weaker global demand, is unlikely to change

much soon, with recessions or sharp growth slowdowns expected in several developed

markets.

Domestic demand for imports of oil, gas, and good commodities is largely inelastic, and

elevated global prices for these will continue to escalate the import bill throughout this

year.

The weakening Ngultrum, which tumbled further to Nu 79.9 against the U.S. dollar on

Wednesday, will raise import costs further. Analysts expect the Ngultrum to scale the

Nu 82 to a dollar mark by the October to December quarter before recovering and the

current account deficit to more than double to around 3% of the GDP this year from

1.2% in 2021-22.

The country also imported fuel worth more than Nu 2.5bn in the second quarter, making

diesel and petrol as the two topmost imported commodities.

Processing units form a huge component of imports, making it to the top 10 list with

more than Nu 2.5bn in the first three months of the year. This too increased to Nu 5.2bn

in the second quarter, forming a Nu 2.7bn increase compared to the first quarter this

year.

Figures, however, show that the country’s trade balance began deteriorating in 2013.

As an import-driven country, a wider trade deficit reduces the incomes of domestic

workers, pushing many into lower income brackets. Families with lower incomes

generally find it much harder to save. Therefore, increasing trade deficits can reduce

national savings.

The country’s gross national savings last year saw a drop by Nu 2.4bn from 28.8bn in

2020.

Policymakers may have little room or solutions to help maneuver the country out of this

vicious cycle, but missteps must be avoided and domestic inefficiencies hurting exports

must be reviewed urgently.